There are several versions told of the Seward County Seat Wars. However, they basically relate the same information with the prime difference being in the account of the killing of Sheriff Sam Dunn of Seward County in the canyons of the Cimarron River near Springfield on January 7, 1892. The factual details of the many interrelated events may never be known with certainty given the passage of time, the involvement of a corrupt district Judge (later elevated to Assistant Adjutant General of the United States Army) and election chicanery freely admitted by some of the participants nearly thirty years after the fact.

The Account of Events by Joe Fuest, Later a County Commissioner

A biographical account of Joe Fuest, who signed the proclamation declaring Liberal the county seat of Seward County, Kansas, under the date of December 10, 1892, recounts the events.

"...After the census enumerator was appointed 'by counting the people, jack rabbits and prairie dogs, the necessary 2,000 population was found so a temporary county organization was effected,' the late Abe K. Stoufer once stated."

Then came the rivalry between Fargo Springs and its neighbor to the north Springfield, now all but forgotten towns near the Cimarron River northeast of Liberal, both of which sought bitterly the county seat. 'There was no politics in the county in those days: it was all 'north' side and 'south’ side,' an old timer who went through those experiences explained it.

As two of the county commissioners and the county clerk were 'south' side men and favored Fargo Springs, as against Springfield, the election was called to be held in Fargo Springs.

This was before Joe Fuest was a county commissioner, but this is the story as told by the late Abe K. Stoufer, the newspaper editor at Fargo Springs at that time. There was bitter rivalry between the two towns. The people of Springfield threatened to come down and capture the polls. To head them off, 50 or 60 Fargo Springs men armed, got into the polling place and stayed all night the night before the election. About sun up between 200 and 300 Springfield men appeared in wagons, on horseback and afoot. The room was already full. All Fargo Springs men were elected as judges and the polls were opened.

The Springfield men refused to vote and going over to Billy Green's grocery store, got a Peat Bros. soap box, and cutting a slit in the top, put it on a farm wagon which was backed up against the building to within six feet of the regular ballot box. All the Springfield contingent cast their ballots in the soap box.

The following Friday, fearing interference, instead of meeting in the courthouse to officially canvass the returns, the county commissioners met out on the prairie on the Springfield townsite and declared Fargo Springs the county seat.

The county records were moved down to Fargo Springs from Springfield immediately. Springfield took the matter to the Supreme Court, which in about a year declared the soap box the legal ballot on the grounds that there were armed forces at the regular polls, so back went the county seat to Springfield in the fall of 1887.

By the time Joe Fuest was elected to the board of county commissioners in the fall of 1891, the Rock Island had built through the south part of the county to Liberal, leaving Springfield high and dry. So another county seat fight was on--this time the movement was to bring the county seat to Liberal.

Sheriff Sam Dunn Stevens county had also had its bitter county seat war between Hugoton and Woodsdale and it was partly an outgrowth of factions in that fight, that resulted in the murder of Sherrif Sam Dunn of Seward county in the canyons of the Cimarron river near Springfield on January 7, 1892.

Sheriff Sam Dunn Stevens county had also had its bitter county seat war between Hugoton and Woodsdale and it was partly an outgrowth of factions in that fight, that resulted in the murder of Sherrif Sam Dunn of Seward county in the canyons of the Cimarron river near Springfield on January 7, 1892.

Mr. Fuest was to take his seat on the board of county commissioners that day. Springfield was in an uproar as he started to the county seat on horseback. On the way he met a friend, A J. Crothers, who told him of the murder and warned him against going on. 'They threatened to kill me. They will kill you.’ Mr. Crothers warned. 'I had to back out of the hotel and my only weapon was this piece of brick which I pciked up.' However, with the same dauntless spirit which stood him in good stead in the trying times to follow, Mr. Fuest determined not to turn from his course. When Mr. Crothers saw that persuasion was useless, he gave Mr. Fuest the piece of brick so he would not be entirely defenseless.

But when Mr. Fuest reached the Cimarron and his horse stopped to drink, he dropped the brick into the water, riding on into town unarmed. On the way he passed the body of the slain sheriff over which two friends were standing guard. The next day two companies of state militia arrived, the one from Sterling and the other from Hutchinson and order was restored. It was three or four days before two prisoners charged with the sheriff's slaying, were brought to Liberal for trial.

'But no one was ever convicted,' Mr. Fuest states. 'One of the jurors said the only way he would convict the accused man would be had he seen the bullet leave his gun and enter Dunn's body.' Mr. Fuest related in recalling the early day history. 'The juror was supposedly a member of the mob.'

The next turmoil in the county came over the proposal to move the county seat from Springfield to Liberal. As stated before, the building of thy Rock Island through the south part of Seward county and the establishment of the town of Liberal on the railroad, had sealed the doom of Springfield and Fargo Springs.

It was plain to see that Liberal, located on the railroad, was the town of the future. So petitions were circulated asking for the calling of an election to vote on the proposition of moving the county seat to Liberal.

An armed guard was kept around Mr Fuest’s home, as they feared he might be kidnapped. Since he was chairman of the board, it would be his duty to call the election. At one time when he was in Springfield, a man pointed a gun at him. He escaped into the hotel.

It was on October 29, 1892 that the board met to consider the petition s presented asking for an election to vote on moving the county seat to Liberal. The petition was found in conformity with the law.

The election to vote on the proposition as to whether the county seat of Seward County should be moved from Springfield to Liberal was duly held on December 8, 1892 and the count of the votes revealed 136 for the relocation and 11 against the proposition.

When the county commissioners met at the Springfield court house on December 10, 1892 to make their official canvass of the returns there was still a feeling of great tension. It was not an easy matter for Joe Fuest, the chairman of the board to get up and announce the returns, with the bitterness which the election had aroused.

Wagons were already lined up ready to move the county records when the result of the election was officially announced. Those accompany the wagons were secretly rejoicing over the fact that they had a ‘stand in’ with the authority who was guardian of some of the rifles and ammunition belonging to the state militia which were stored in the county, which authority had made them a generous loan of a number of these. However the same party had also played confidant to the Springfieldites, and when the county commissioners went to the hotel before the meeting for the official canvass of the votes, they found twice as many guns under the stairs as they had.

'When the board meeting opened Charlie Mayo said to me, 'You better get up and give the result of the election,' Mr. Fuest recalls. 'I hated like blazes to do it,' he added. But he proceeded to announce the results by townships and the total. after the canvass was made.

As soon as the results were read the loading of the wagons began. Each officer picked his crew and kept his records separate.' Mr. Fuest states. Only one officer, P.F. Vessels, the county treasurer, refused to move, on the contention that the election was not legal.

'There was no trouble until the wagons were about a mile or so out of Springfield,' Mr. Fuest states, 'then the Springfield side fired some shots into the air.' From then on there was no more trouble and the county seat proceeded on wheels to Liberal, its permanent location, after six years of more or less bitter contention following the organization of the county and the rivalry between Fargo Springs and Springfield and then Springfield and Liberal.

When the county records were moved by wagons on December 10, 1892, from Springfield to Liberal the seat of county government became a big frame building straight west of where the present courthouse is located on North Washington Ave., according to Mr. Fuest.

But it was several months after the county seat was moved here until county affairs settled down into a quiet routine. In fact, as late as the following summer, some of the Springfield supporters had not yet submitted to defeat.

The record of the county commissioners' meeting of July 6, 1893, tells of proposals submitted for drastically cutting the salaries of county officials. The proposition was offered under the pretext of hard times and poor crops, but Mr. Fuest recalls that it was but a blazing up of the dying embers of the county seat fight.

Mr. Fuest became irate over the injustice of the whole matter. He broke up the meeting by throwing a dog straight in the face of the attorney who had come from Topeka with the exclamation ''You got less sense than that dog!"

The Account of T.J. McDermott, Newspaperman, Businessman and Admitted Election Rigger

T.J. McDermott, who arrived in Liberal about 1888, dictated the following information to his daughter so that early happenings in Seward County would be preserved. He was editor and owner of the Liberal Lyre, a newspaper, until he sold it to Abe Stoufer, owner of Liberal News.

Mr. McDermott recalled when Liberal was declared the county seat. He noted that 1892 was a campaign year and that Sam Dunn ran for sheriff that year. Mr. McDermott wanted to see him elected, and all of his men were elected.

In 1894, Liberal was trying to get the county seat away from Springfield, and there was much competition and some bitterness about it. Arkalon was supposed to be neutral; but when word quietly got around that if Liberal got the county seat, their houses and businesses would be moved to Liberal. They would be given lots to put the houses on and support for the different firms. They voted for Liberal. Springfield claimed the election to move the county seat wasn't legal and didn't vote. Liberal got the county seat by a big majority, and the judge decided that the election was fair.

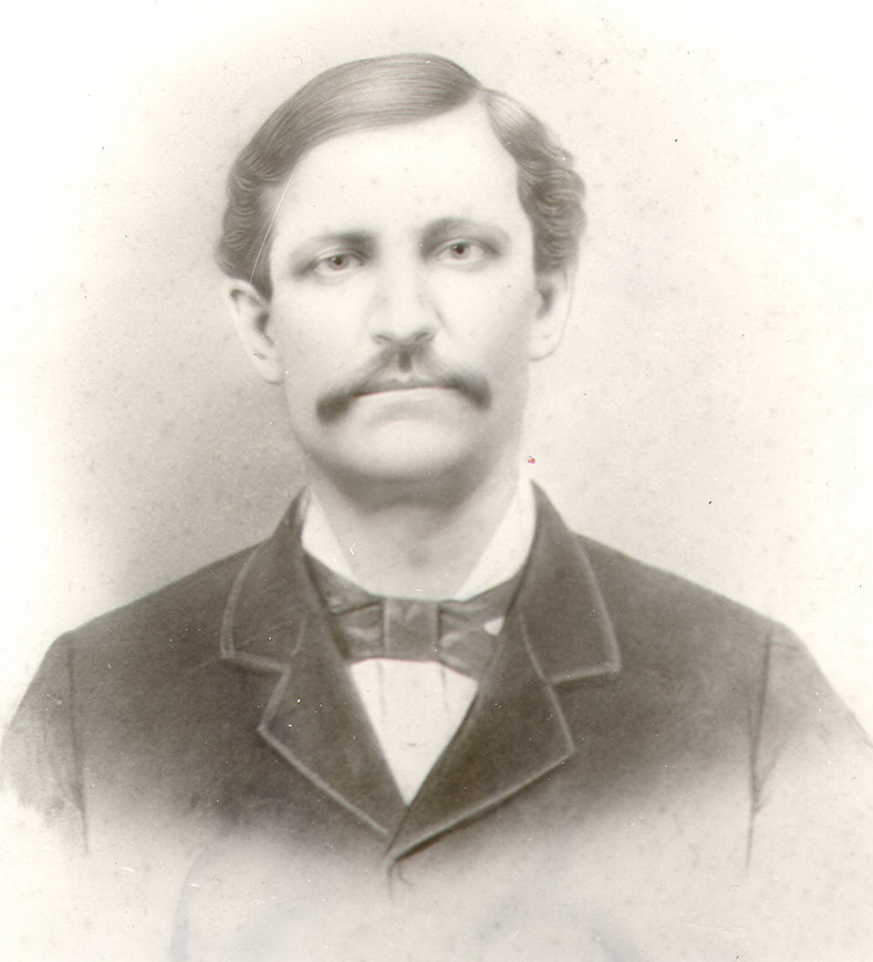

Judge Theodosius Botkin

Judge Theodosius Botkin

Mr. McDermott also gave an account of the killing of Sheriff Dunn. In 1894, Roy Guymon ran for sheriff and was elected but the election was contested and wasn't decided until the Saturday before New Year's Day. There was court on at Springfield, and a big crowd was there. Judge Theodosius Botkin was disliked by the Stevens County crowd over some decision there and the opponents of Guymon joined them in some way. When the judge arrived home, he found a note in his pocket threatening his life when he returned to court on Monday. It said he would be killed at a certain place along the road going along the head of the canyon that leads up from the Cimarron River. Judge Botkin organized his friends to protect him, and about four o'clock Monday morning Sam Dunn, Roy Guymon, Sid Nixon, George Caine Joe Larrabee and his father, and Bill Custer went to the place and hid in the draws.

After waiting for a long time and looking for the enemy, they about decided that the whole thing was a hoax and were just going to give it up and go back to Springfield when Sid Nixon saw what he claimed were "sixty men'' with guns and gave the alarm. Sam Dunn challenged them by calling out, ''Who are you and what do you want?" They answered with the call, ''Who are you?" and Dunn said, "I am the sheriff and demand peace." They replied with two shots, and Dunn was killed and fell to the canyon below. From the examination later, he must have received both shots for one entered one side of his body and the other, the other side. After he fell there was another shot from above, and this shot entered the body at the knees and went up through the body to the chest, as he had fallen head down.

When Joe Larrabee offered to surrender, they told him to throw down his gun and go home. He did so, turning to the right and someone called out, "Oh, Bi, tell Joe to turn left and avoid the other wing of the party." This was the only name used in trying to convict one man of this name, known to be on that side, but no conviction was made.

Joe Larrabee went to Springfield and gave the alarm, and everyone in town armed himself and went to the scene of battle, but no one was found. Someone saw a large party of men go from the Fargo schoolhouse north and turn west at the Springfield schoolhouse, but they never were caught and the mystery of who the gang was is still unsolved.

Botkin, thinking a mob was trying to do great harm, rode a horse to Arkalon and wired the Governor for troops. Two companies were sent the next day. A coroner's jury was organized, and T.J. McDermott was made foreman. Joe Larrabee was the best witness. Many were so excited they couldn't remember much of what happened, but he was perfectly calm and could tell the details clearly. The whole thing was the outgrowth of the old Stevens County Seat war and the killing of Sam Woods, a prominent lawyer. But the mystery was never solved.

Account of the Topeka Capitol-Journal, December 21, 1958, 66th Anniversary of the War

The bloody six-year county seat war between Springfield and Fargo Springs, two prairie towns long gone from the Kansas scene, ended 66 years ago this month.

If there is a beginning and an end to such an affair, it might be said that the night riders along the Cimarron disappeared forever from Seward County on December 8, 1892, when by a quirk of fate Liberal, the new town on the rail head 18 miles south of Springfield, became the county seat.

Within three hours after the official vote count, teams and wagons were on the road to the new county seat with all the records, writing the final chapter to one of the bitterest fights ever waged by two frontier towns.

The beginning might be with the land promoters who created the two little towns only three miles apart on the prairie, each group believing the new railroad would go through their town and bring great wealth to the promoters. As the town grew through the efforts of the clever promoters and their henchmen, each vied for the honor and the spoils that would come from becoming the county seat. Each promoter found it easy to recruit professional gun-fighters and night riders from the no-man's land in near-by Oklahoma territory.

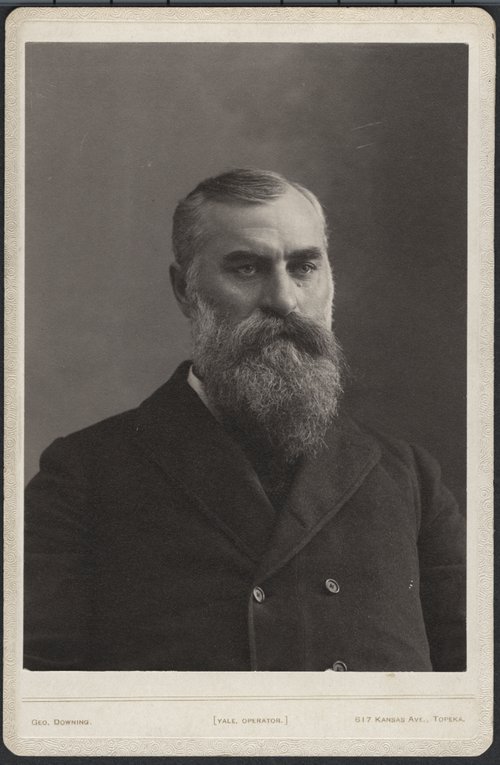

Lee Larrabee

Lee Larrabee

The late Lee Larrabee of Liberal, a noted historian of the Southwest believed there were a dozen or more killings during the bitter conflict that were never reported. The High Plains in the decade before the turn of the century was a hard land. There was no place for weaklings. Men could be slain by their enemies far out on the lonely prairies or in the rough, deep draws along the Cimarron water course and never be missed or found.

With men from Fargo Springs and Springfield on the warpath, it wasn't long until every family in the Cimarron country was caught up In the violence of the feud between the two towns. There are few, if any, alive today who participated in this lurid period of Kansas history, but the hatred engendered during the Fargo Springs - Springfield conflict and the bizarre killing of a Seward County sheriff and attempted assassination of District Judge Theodosius Botkin is remembered by the last residents of the old townsite of Springfield.

Mrs. R. Wallace, who, with her husband, has operated a store and filling station on Highway US-83 for 27 years at the site of old Springfield, recalls when it was a town of more than 1,000 inhabitants with two hotels, a large brick school, newspaper, every kind of business and many two-story buildings.

She pointed toward the south-- 'It was right over there a short ways along the river that Sheriff Dunn was shot. My father was there that terrible night.' The curtain was raised on the ensuing drama by Governor John A. Martin when he appointed county commissioners and called for the organization of Seward County. They met at Springfield on July 3, 1886, organized the county, and called for an August 5 election to vote on a permanent location for the county seat.

Polls were set up at the Prairie Owl newspaper office in Fargo Springs and when the Springfield people arrived to vote they found that in order to do so they must hand their ballots through a slit in a window lowered from the top in such a manner that it was impossible to see who was receiving them. Such a procedure was met with immediate resentment by the Springfield partisans and they set out to erect their own polling place.

They pulled one of the wagons into the middle of the street near the Prairie Owl, secured a 'Lenox' soap box from a near-by grocery and set it in the wagon for a ballot box. There, under a boiling Kansas sun, and surrounded by fighting and name-calling and violence, the Springfield partisans cast their votes in their own free way. But it was to no avail, since the majority of the commissioners favored Fargo Springs and considered the Prairie Owl votes the legal ones.

The county seat was moved to Fargo Springs, where it remained until June, 1887, eight or 10 months after the election, when the Supreme Court ruled the ‘Soap Box' votes to be legal and ordered the county seat back again to Springfield.

Ironically, both towns were destined to lose, for shortly after the election the railroad builders changed their plans and turned their tracks southwest missing both feuding towns.

Fargo Springs' death knell was sounded with the loss of both the county seat and the railroad, and her businessmen fled immediately to Liberal with its promise of prosperity and growth.

But the hatreds and bitterness sparked by the county seat conflict and the court decisions in Seward and other neighboring counties would not die down.

It was on February 18, 1888, that the attorney general began suits in the Supreme Court against Seward County officials for allowing fraudulent claims, issuing bonds without vote, receiving bribes, and systematically robbing the people of the county.

Tension reached the breaking point sometime during the Christmas season of 1891 and a group of bitter Springfield men with special hatred toward the controversial district judge, Theodosius Botkin, met one night seeking vengeance and plotted the bushwhacking of the judge as he rode to Springfield to open the January term of court.

Botkin, a huge man, had fearlessly pushed his way into all disputes in the southwest Kansas frontier, making enemies at every turn. The preceding spring he had been indicted by the House and tried by the Kansas Senate.

The secret ambush was well kept until shortly before the murder was to take place.

Sheriff Dunn heard about the plot from Undersheriff H.P. Larrabee, Lee's father, only a few hours before it was to happen and with his deputies walked south from Springfield and onto the plains where the Homestead Road led into the Cimarron canyons. They concealed themselves along the rimrocks awaiting the assassins in the bitterly cold January pre-dawn. Just before daybreak the hoodlums showed up accompanied by 50 or so men who trailed along to watch the kill.

Dunn, fearing for Botkin, ordered a few of his men to slip away to warn the judge. By accident, the Dunn men stumbled into some of the Springfield men and shots were fired in the excitement. Dunn climbed out of his concealed place and ordered the mob to disperse and was answered by a volley of shots. He fell fatally wounded.

It was said that the mob panicked and continued to fire more shots into the prostrate body of Sheriff Dunn as he lay dead or dying, before they melted away into the dawn. Feeling ran high in Springfield and the atmosphere was tense as anti-Botkin men and Botkin sympathizers loitered around town in groups ready to explode into more violence. News of the dramatic events were telegraphed to Governor Humphrey and he immediately ordered the National Guard from Hutchinson to the scene and Springfield was placed under martial law.

And so ended a dramatic period on one of the little-known Kansas frontiers.

The Account of Aleen House, Seward County Register of Deeds, from the Court-House Clarion

A fourth account explaining how the courthouse was finally located in Liberal was written by Aleen House, Register of Deeds, Seward County, Liberal, and was published in the Court-House Clarion. It is quoted directly.

Seward County, like most all other western counties, was the scene of several county seat fights in its early history. Towns no longer in existence, whose memory is all but forgotten, flourished in those days and struggled long and bitterly to secure the county seat which meant prosperity and continued growth to them.

Bribery in the form of promise of town lots in the would-be county seat to those supporting its claims, is one of the accusations made against these early day enthusiasts, and it is certain that firearms of various descriptions played no small part in the contest.

Springfield was designated as the county seat by the governor in July, 1886, when the county was organized and officers appointed to serve until a called election, August 5, 1886. Then the location was to be determined by vote. After the vote was canvassed by the county commissioners and the famous soap box ballot thrown out, Fargo Springs was declared as having a majority and the records and the officers moved there.

But the case went to the supreme court, which declared the soap box ballot the legal one on account of intimidation and the officers again packed up the records and returned to Springfield. Here the county seat remained until 1892.

December 8, 1892, the location was again put to a vote, the rival towns this time being Springfield and Liberal. The following account of the result appeared in the Liberal News, December 15, 1892.

'The official canvass of the county seat vote was made last Saturday showing 125 majority for the proposition. Thirty-one persons from Liberal and eight from Arkalon went to Springfield to witness the canvass. Five wagons were taken along to remove the records to Liberal, if so ordered by the commissioners. After the canvass the vote was announced and the commissioners ordered the books, papers and county property removed at once. Several teams were procured and it was but a short time until the county seat was on wheels, merrily rolling towards its future home. Everything was quiet and orderly throughout' However, interference had been feared and the Liberal delegation was well armed.

The former Pacific Hotel building was secured for the new courthouse. This building was let to the county free of charge by the Kansas Town & Land Company, the principal as underlying cause for this generosity being a desire to draw as much of the town business as possible to that street. This courthouse, which served until the present one was erected in 1907, was a two story frame building constructed in not too substantial fashion. In July, 1907, it was declared unsafe for the purpose and the first steps were taken toward the erection of a permanent budding.

The building was completed at the cost of $15,000 and was ready for occupancy in April, 1908 and the final move of the records made then. The old courthouse was again converted into a rooming house which was destroyed by fire in 1909.

Such is the history of the Seward County Seat Wars.

Sources include:

Southwest Daily Times, Liberal, Kansas, June 22 and June 28, 1948

Recollections of T.J. McDermott

Topeka: The Historical Records Survey, ''Seward County Clippings'' Vol. 2, pp. 97-100

Topeka Capitol-Journal, Topeka, Kansas, December 21, 1958

Court-House Clarion by Hazel, ''The Courthouse and How It Was Finally Located in Liberal, Kansas,'' submitted by Aleen House